Foreword

I am writing this essay for the same reason I do most of my writing: to jot down a self-consistent framework for thinking about a certain topic that I can later refer to and rely upon, so that I can avoid being hoodwinked by the often chaotic and contradictory discussions surrounding said topic.

Censorship and freedom of speech are certainly one such topic. On one side of the planet, totalitarian regimes are throwing people in jail for the most miniscule slight against the government; on the other side, presidents are getting unilaterally banned by social media platforms, to the cheers of some and the lament of others. If you simply believed every demagogue online, you would simultaneously believe that everyone has a natural right to make their voice heard, and that we should silence anyone who is Russian/transphobic/Republican/Muslim/[insert your favorite bogeyman here] because they’re unequivocally evil and nobody should ever listen to their words.

Most accept such doublethink since they find the topic to be too complicated and abstract, but I beg to differ. The topic is nuanced and has a long history of various viewpoints, but I believe that any rational person is capable of constructing a framework for understanding it based on nothing more than first principles and logical deduction. To quote Plato, “If you do not take an interest in the affairs of your government, then you are doomed to live under the rule of fools.” If we left freedom of speech, arguably one of the most important freedoms we possess, to the hands of bureucrats seeking to increase their power over us or demagogues who fool mobs into serving their own selfish interests, then humanity has no hope indeed.

1. Why we defend freedom of speech

Why do we defend our freedom of speech?

The first reason is that freedom of speech is the natural state, and what requires justification is the deprivation of it, not the other way around. Speech is a natural and essential part of our everyday lives, and the impact of losing the ability to freely voice our thoughts and opinions can range from a sense of disgust to clinical depression. We were born with mouths, ears, and brains, so we want to speak and be heard and feel sad when we can’t do so. It’s hardly rocket science.

The second reason is that freedom of speech is vital to the free exchange and debate of ideas and thus the progress of our society. New ideas are frequently viewed as radical or even immoral through the lens of the establishment and vested interest groups; if we shut them down for that reason, innovation will be greatly stifled, and societal progress will be slowed.

The third reason is that freedom of speech is necessary for making informed decisions. In order for people to make sound decisions, they need to have access to information that is true and accurate. If the truth is censored, people will unknowingly make decisions and take actions that are against their own interests.

2. Censorship is ethically untenable

Why is freedom of speech considered a universal human right when similarly common and valuable acts like, say, driving a car are heavily regulated? If there was a new law saying that we must have a license in order to speak publicly, we would protest it as a grave violation of our freedom of speech, but we accept the fact that we must have a license to drive without saying that it violates our right to drive, and we don’t feel like our right to drive is being violated by the license requirement. What makes freedom of speech special?

In my opinion, censorship is ethically untenable. The first reason is that there cannot exist a standard for acceptable speech, except in certain edge cases. It is easy to agree on a standard for acceptable driving: you should drive on paved roads under the speed limit, obey traffic signs and signals, and generally not crash into anyone or anything. It is also easy to agree on what constitutes unacceptable driving: driving too fast, running red lights, crashing into pedestrians, etc. The question “What is acceptable speech?”, in contrast, is more akin to open questions like “What is the meaning of life?”, and accepting any concrete answer entails buying into a certain ethical framework. Establishing a standard for acceptable speech and censoring speech based on it means forcing everyone to accept the same ethical framework, which in itself is unethical under most standards. Furthermore, ethical frameworks change over time, and thus any standard for acceptable speech must also be prepared for change alongside ethics, but censorship often means that any discussion of the faults of the system of censorship itself is censored. Thus, censorship entails forcing everyone to accept a single, static ethical framework, which is both ethically problematic and practically stupid. The only case where censorship is reasonable is when the subject being censored is universally viewed as reprehensible, such as child pornography, but that’s the exception and far from the rule.

The second reason is that censorship necessarily leads to dystopian conditions. It is easy to discover and punish bad drivers: speed radars and video cameras can monitor major intersections for traffic rule violations, and police cars can roam around areas with heavy traffic to check for bad drivers. To discover and punish bad speech, however, requires a much heavier hand. We would have to monitor all speech as well as pass judgement on each piece of speech, with enough efficiency to censor “bad speech” before “bad outcomes” occur, which necessitates a massive all-encompassing bureaucracy and surveillance infrastructure. As we all know, “power corrupts, absolute power corrupts absolutely”; if such infrastructure were constructed, eventually it would fall into the wrong hands and be abused for unethical purposes. If you think fascists are bad and we should build a surveillance and censorship infrastructure to shut them all up, just imagine what will happen when fascists take over said infrastructure and shut you up instead. They’ll probably do a lot more than shut you up, though.

Thus, we conclude that censorship is impractical, ethically dubious, and almost certainly results in horrible outcomes.

3. Why does censorship happen anyway?

Despite the fact that freedom of speech is obviously valuable and censorship is obviously bad, censorship happens anyway, even in the supposed “free world”. Why?

There are two common reasons why censorship happens. Firstly, an entity powerful enough to censor will often do so to further its own interests. For example, an authoritarian regime would censor its wrongdoings and faults and silence critics and dissidents so that its rule is protected. A corporation might censor bad press about them by paying off and/or threatening the media. Censorship based on such reasons is obviously bad and is commonly viewed as such.

The second reason is more insidious and relates to censoring something because it is seen as ethically reprehensible by the censor. Such censorship is typically phrased as “fighting misinformation” and “eliminating hate speech”. As I’ve discussed before, censorship for ethical reasons entails forcing the ethical framework of the censor onto the censored, which itself is unethical. However, the champions of such censorship often recognize this but justify the censorship by saying that the censored subject is universally seen as unethical, which makes it okay since they’re not forcing an ethical framework onto others. Such champions are, under most circumstances, misguided because they mistakenly think that everyone else also views the subject as unethical when it’s far from the case. One thing to always keep in mind is that the spectrum of opinions is far wider than you usually think. If an opinion exists, then somewhere out there someone will hold that opinion. If some people can legitimately think the Earth is flat, they can also think that homosexuality is a sin. Assuming your personal ethics are universally accepted is simply hubris.

Furthermore, they do not consider the massive negative impacts of building up a leviathan surveillance and censorship infrastructure. Giving the authorities the power to censor speech you don’t like (“hate speech” “misinformation” etc.) might make you happy, but this power is a double-edged sword, as all powers are, and it can just as easily be used to ban speech you do like.

Do you really trust the soulless bureaucrats and senile politicians to always “do the right thing”?

I don’t think anyone in their right mind would say yes.

4. Private platforms are capable of violating freedom of speech

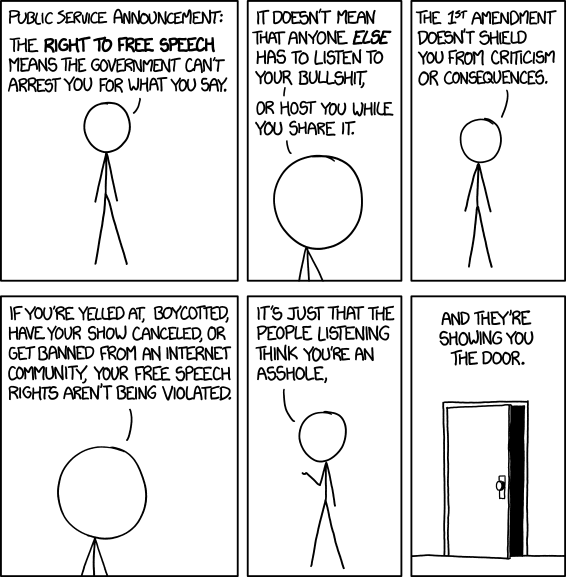

Surprisingly many people, perhaps even the majority, hold the view that only governments are capable of violating someone’s freedom of speech, whereas private platforms (such as social media) are logically incapable of doing so. This view is, in short, false.

Its adherents often cite the first amendment of the US constitution as the justification, but I find this stupid. It may shock some people when I say this, but the US constitution is not universally applicable and is not the final word on anything other than American jurisprudence. The US does not have a monopoly on defining freedom of speech. The US constitution preventing the US government from censoring but not private entities has zero bearing on this debate, period.

Another argument goes like this: as long as someone is not using violence to physically prevent you from speaking or publishing, your freedom of speech is not violated. Thus, private platforms are incapable of legally violating your freedom of speech since they have no legal power to use violence. Even if you are banned by a private platform, you can always switch to another platform or build your own platform and continue exercising your freedom of speech.

This argument may appear sound at first glance, but it is in fact a misleading oversimplification and overall wrong.

Even without thinking about it too hard, most people can intuitively feel something wrong with this argument. After all, if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it is probably a grave violation of your freedom of speech. The end result of whatever it is that social media platforms are doing is that certain groups of people are being silenced, their voices inaccessible to most people, which is the same as the consequence of censorship by governments (minus the violence). A group of unelected individuals, answerable only to their own profits, are arbitrarily silencing people; how can any rational person see this and think “at least it’s not our elected officials doing it”?

There are three reasons why this argument is deeply flawed. Firstly, its definition of freedom of speech is binary, which is overly narrow and inevitably leads to flawed conclusions that do not match reality. It frames freedom of speech as something that you either have or don’t have, and regards anything short of making it physically impossible for you to speak as “not violating freedom of speech.” This is clearly not true: as an extreme example, if I start shouting nonsense next to you using a loudspeaker whenever you try to talk to someone, by this definition I wouldn’t be violating your freedom of speech, since it’s still theoretically possible for you to shout louder than I do, but you’d obviously be silenced in actuality. Sure, if you actively erased someone’s speech from the public forum and prevented others from ever coming into contact with them, it is still theoretically possible for them to build their own platform and spread their word, but it is practically impossible; it would not be a complete deprivation of their freedom of speech, but it is still a deprivation of their freedom of speech. Silencing someone and locking someone up are both violations of their freedom of speech, just like how punching someone and killing someone are both acts of violence.

Secondly, its definition of freedom of speech does not include our right to freely access the speech of others, but this right is an essential part of freedom of speech. As I’ve mentioned before, one reason freedom of speech is important is that it enables the free discourse of ideas, and any free discourse not only requires the freedom of the speakers to speak, but also the freedom of the listeners to listen. Censoring an idea would not only be an intrusion on the freedom of speech of the speaker, but also that of the potential listeners who would’ve wanted to discuss it. Censorship is not just about covering mouths, it’s also about covering eyes and ears. If you covered up everyone’s eyes and ears, even if speakers can theoretically build their own platforms and speak there instead, you’d still be violating the freedom of speech of those whose eyes and ears you’re covering.

Thirdly, it does not consider the fact that private platforms are, in most cases, owned by small groups of people who don’t share the same views and interests as the users of the platforms, and the decision to remove undesired speech from the platform ought to be collectively made by the users rather than the owners. Whether an idea is acceptable to a forum should be decided by the actual people speaking and discussing in that forum, not whoever owns the building; just like whether a law is acceptable to a nation should be decided by the actual people living their lives there, not whoever owns the land their houses are built upon (who may be foreign). The folks taking the position that “private platforms can do whatever they want on their platform” are essentially the monarchists of the free speech debate, their argument analogous to “monarchs can do whatever they want to the country they are sovereign over”. These folks neglect to acknowledge that the value of a platform for speech is derived not from the owners of the platform, but from the speakers and their speech. As the ones who contribute the most value to the platform, the speakers should be the ones to decide the rules of the platform. For this reason, all public forums should be owned by the public, and the status quo of privately-owned forums is an aberration to be corrected rather than the basis for a theory of free speech. Belief in the property rights of private forum owners is diametrically opposed to belief in freedom of speech.

Thus, I conclude that yes, private platforms are perfectly capable of violating your freedom of speech via censorship. And that’s exactly what they’ve been doing all this time.